INDIAN TRADING POSTS

LIVING LEGENDS OF THE OLD SOUTHWEST

Story by Kathryn Burke

Photography by James Burke

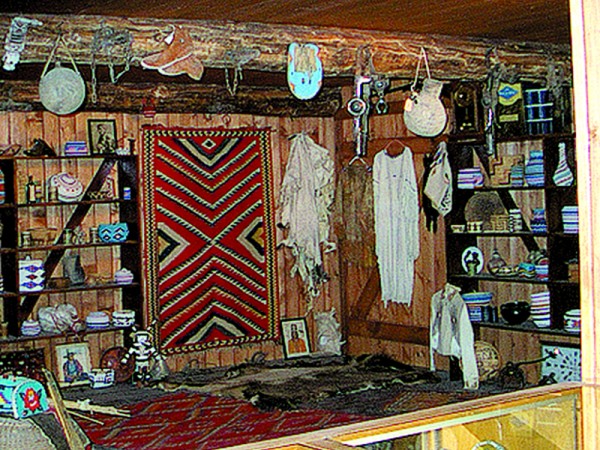

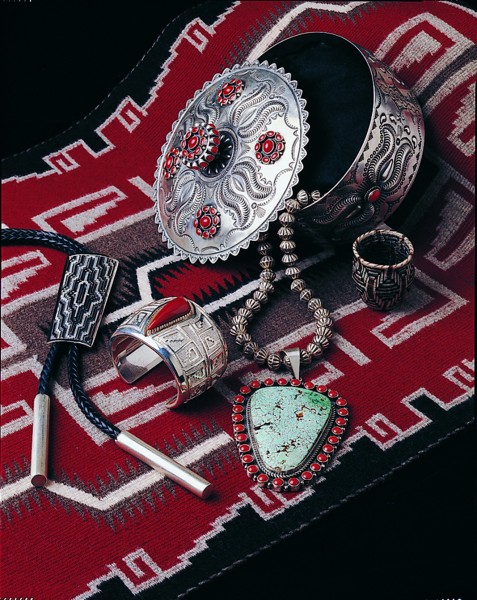

They are colorful, bustling places, born of necessity and unique history and today possessed of unique scents, sounds, shapes. —Old leather, wool, the tang of vegetal and chemical yarn dyes. —Worn wood, tarnished silver patined with years of use, rows of rugs and saddles. —Silver jewelry inlaid with turquoise, coral, and the wink of colorful cut stones —Woven baskets, hand-crafted pots, carvings, fetishes. Everywhere there are shouts of laughter, quiet murmurings in guttural, breathy phrases. In the parking lot, where once horses neighed and stamped and munched hay while their riders swapped goods and stories inside, is the throaty flow of an endless parade of pickups (replacing wagons) carrying families come to trade. And the color, swirls of velvet beneath silver, brightly patterned scarves and shirts, sparkling concho belts, hat bands and adornments, all worn with festive pride.

Indian Trading posts are a living legend in the Southwest. Begun in the 1700s and supplying the native peoples with whatever they needed and buying from them all that they produced, these posts were—and still are—social centers as well as provisional supply depots. Going to the trading post, for many, is akin to going to market, a chance to meet, greet, catch up on gossip, sell, trade and stock up on basics before the long trek back home. “Many of these posts were begun by Mormon men sent to establish missions and open avenues of commerce with the ‘lamonites’ or Native American people of the region,” according to Bruce Burnham, fourth generation trader, Sanders, Ariz. Many of today’s posts also serve as non-institutional bankers to Native Americans. “We are the bankers for the Navajo,” explains fourth generation trader Ellis Tanner, Gallup, NM. “Their way of writing a check is to take off a bracelet and pawn it.” “Once we’ve got someone in the computer, it takes only a couple of minutes to transact a trade,” adds fourth generation trader Glenn Leighton of Notah Dineh in Cortez, Colo.

Indian Trading posts are a living legend in the Southwest. Begun in the 1700s and supplying the native peoples with whatever they needed and buying from them all that they produced, these posts were—and still are—social centers as well as provisional supply depots. Going to the trading post, for many, is akin to going to market, a chance to meet, greet, catch up on gossip, sell, trade and stock up on basics before the long trek back home. “Many of these posts were begun by Mormon men sent to establish missions and open avenues of commerce with the ‘lamonites’ or Native American people of the region,” according to Bruce Burnham, fourth generation trader, Sanders, Ariz. Many of today’s posts also serve as non-institutional bankers to Native Americans. “We are the bankers for the Navajo,” explains fourth generation trader Ellis Tanner, Gallup, NM. “Their way of writing a check is to take off a bracelet and pawn it.” “Once we’ve got someone in the computer, it takes only a couple of minutes to transact a trade,” adds fourth generation trader Glenn Leighton of Notah Dineh in Cortez, Colo.

Try that at your local bank sometime when you need a quick loan!

A little over 200 years ago, Native American peoples and the few whites who ventured to the raw and challenging Southwest depended on a loosely connected trail of trading posts to swap the fruits of their special skills for staples, tobacco, guns and horses. Animal skins and hides, beaded work, woven blankets and rugs, pottery, personal adornments were traded for items brought by team or wagon train to the far outposts. Often the freighters became the traders, building a permanent structure to replace the back of their wagon for doing business. Soon they added conveniences for visitors and customers, often providing lodgings and food—a sort of modern-day wilderness motel and cafe stop. “My Uncle Willard had a hogan outside,” Leighton explains. “People would come in from a great distance, bringing their families with them. He’d put them up in the hogan, feed them, and then in the morning, when they were rested, do the trade. It worked out for everyone that way.”

A little over 200 years ago, Native American peoples and the few whites who ventured to the raw and challenging Southwest depended on a loosely connected trail of trading posts to swap the fruits of their special skills for staples, tobacco, guns and horses. Animal skins and hides, beaded work, woven blankets and rugs, pottery, personal adornments were traded for items brought by team or wagon train to the far outposts. Often the freighters became the traders, building a permanent structure to replace the back of their wagon for doing business. Soon they added conveniences for visitors and customers, often providing lodgings and food—a sort of modern-day wilderness motel and cafe stop. “My Uncle Willard had a hogan outside,” Leighton explains. “People would come in from a great distance, bringing their families with them. He’d put them up in the hogan, feed them, and then in the morning, when they were rested, do the trade. It worked out for everyone that way.”

The hogans are gone, and in the case of traders such as Tanner in Gallup, the massive livestock pens, slaughter house and inside, isles of hardware, groceries and health products (for once these traders supplied everything).

“I used to buy 10 thousand head of lambs in the fall,” says Tanner. “The pickups would be lined up clear around the building and down the road. We’d ship the animals to farmers, mostly in Kansas.” But the Navajo sheep population is less than 15 percent of what it once was, and produce, groceries and other staples are available in local chain stores. “I still keep some fresh mutton,” Tanner adds, “but mostly my stock now is Indian arts and crafts.”

It’s a familiar refrain in the still-remaining trading posts. Now, most of the trading is for hand-crafted items, and like as not, the medium of exchange is cash rather than a pawn slip. (Or the “tin money” called seco minted by and redeemable to individual posts in the late 1800s.) The social center aspect is still much in evidence, however. Stop by on the first or third of the month, pay day for many Native Americans, or any Saturday, and you will see a colorful array of customers inside and family-filled pickups in the parking lot. The men are decked out in bright bandannas, conchoed belts and hats, high-heeled boots. The women are festive in jewel-toned velvets, their long hair pulled into a neat bun fastened with a silver clip. Many wear their wealth, silver and turquoise ringing their neck, clustering on fingers and ears. They are all making the trade circuit.

As in most things Native American, the trade trek is circular. They will stop to trade and visit at many posts before heading back home with hay and groceries in place of the weavings, pots or jewelry they left behind. Along the way they may visit Hubble or Burnham in Arizona, Notah Dineh in Colorado, perhaps one or more of the Ortega’s in any or all of the Four Corner states. Some will go several hundred miles, seeking traders who pay a high cash price for top-of-the-line crafts. Highly skilled basket weavers may go to Twin Rocks in Bluff, Utah, where the Simpson brothers are known for buying museum and collector-quality baskets. Others, especially potters, will hit the Indian markets in Santa Fe or Albuquerque to sell outright to wholesalers who sell to the consumer-oriented, glorified gift shops that don’t trade or buy directly from Native Americans. A lot of them will eventually turn up in Gallup, where there are four active, competitive traders, two of them fourth and fifth generation traders from the Tanner family.

“They come from a huge area, driving as much as 200 miles to get here,” says Ellis Tanner. “Flagstaff and Farmington are bigger towns, but Gallup has always been a trade center. Draw a circle 100 miles in any direction, with Gallup in the center, and you’ll see our trade area. The business has changed a lot,” he adds, “as most things have. We don’t supply much meat and groceries any more, now it’s income tax services and pinon buying, arts and crafts, and the pawn.”

“They come from a huge area, driving as much as 200 miles to get here,” says Ellis Tanner. “Flagstaff and Farmington are bigger towns, but Gallup has always been a trade center. Draw a circle 100 miles in any direction, with Gallup in the center, and you’ll see our trade area. The business has changed a lot,” he adds, “as most things have. We don’t supply much meat and groceries any more, now it’s income tax services and pinon buying, arts and crafts, and the pawn.”

The latter is unique to the trading post business. Many Navajo and other Native Americans use the posts as a repository for their valuables such as jewelry, saddles, rugs and firearms. The posts provide a secure, climate-controlled storage area. Pawners may leave valuables there for a short term, when they need a quick loan, but they often purchase, collect and store items there. Or they simply pawn things for safekeeping until needed.

“In the fall, just before hunting season, they take out their guns,” Leighton says. “Then, when the season is over, they put them back again until next year.” Pawn laws are different in each state, allowing the trader to lend money and collect interest until the pawn is picked up by its owner or “goes dead” (similar to a loan or “note” being “called” in the banking business.) Unlike commercial lending institutions (banks, finance or credit card companies), where called loans, repossessions and relentless pursuit by bill collectors are not uncommon, less than two percent of pawn goes dead.) Traders tend to accommodate their customers, especially in unusual circumstances such as bad health or cessation of employment, and keep the pawn going until it can be redeemed.

Virtually all of the traders interviewed for this story (including those who only buy outright) have long-standing personal relationships with their customers. The trading business is based on trust and mutual respect that has endured for generations, and for entire lifetimes within each generation. “You trade by decades,” Bruce Burnham explained.

Virtually all of the traders interviewed for this story (including those who only buy outright) have long-standing personal relationships with their customers. The trading business is based on trust and mutual respect that has endured for generations, and for entire lifetimes within each generation. “You trade by decades,” Bruce Burnham explained.

“The first decade you are learning how to be a trader, sell groceries, sweep floors. During the second decade, you start making management decisions, are working toward profit. By the third decade you are adopting yourself into their culture, becoming more community minded, estab- lishing terms of mutual respect. In the fourth decade, the customers come in and start calling you “shi’yazh” (my son). You’ve watched their kids grow up from the cradle board. As they have watched yours. By the fourth decade, you are a community patriarch. The profit motive recedes with each decade after you are established—you become more concerned with the welfare of your customers. The fifth decade, which I am approaching, is not good for business. The pressures are off, family raised, you’ve become an integral part of the community with which you are trading.”

Few true Indian traders remain. Even fewer are fifth or sixth generation traders who deal directly and trade rather than purchase outright for cash the Native American arts and crafts they sell. Among those remaining are Lynn Tanner in Gallup, Sheri Burnham in Sanders and several Ortega’s scattered throughout the Four Corners area. With the advent of chain stores and easy accessibility of convenience stops, the need to trade for food and necessities is fast disappearing. Another major change is the pickup. Payments are due monthly to a bank. Filling the insatiable fuel tank calls for cash. The time of the traders is about gone. “But as long as a few of the old ones remain, we will have a place here,” says Burnham, referring to the non-English speaking Navajo whom he, like other traders, helps with personal business. The few traders who are left, like Ellis Tanner and Bruce Burnham, work hard to help the young Native Americans retain pride and place, remembering and perpetuating their culture and language. And the non-traditional traders, like Barry and Steve Simpson, who deal directly but in cash, help too, insuring that Indian Arts and crafts will always have a market, and their makers a source of income.