Hardrock Mining

early prospectors came to the San Juan Mountains in 1860

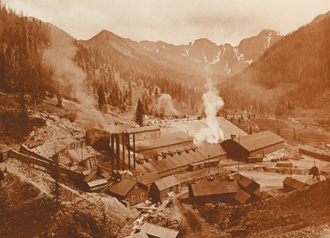

Story by Scott Fetchenhier. Image courtesy San Juan Historical Society

All content © San Juan Publishing Group, Inc, All rights reserved.

[SW Colorado] The earliest prospectors came into the Silverton area in the summer of 1860. Though finding only small amounts of gold, they triggered a rush for the San Juans in the winter of 1860-1861 that ended in devastation for many, due to starvation, blizzards, Indians and exhaustion. Those who made it to the upper Animas River that spring found little gold, and most left by early summer.

Men did not venture into the area again until 1870. After a small group of prospectors made rich strikes in surrounding gulches, swarms of men poured into the area in the early 1870s. They discovered numerous veins containing gold, silver, lead, zinc and copper. Small towns sprang up overnight near the newly found mines. The Brunot Treaty, signed in 1874, forced Ute Indians from the area.

Harsh winters, poor roads, expensive transportation by pack animals and the lack of efficient mills and smelters hampered early mining. After several years, the rich ores near the surface were exhausted, leaving uneconomical lower grade ores. The arrival of the train in 1882 changed Silverton’s economics. With cheaper transportation costs, the lower grade ores could be mined.

The discovery of rich silver ore in the Red Mountain district in 1881 triggered a mining and railroad boom that lasted for over a decade. It all came to a sudden halt in 1893 as plummeting silver prices forced the closure of many mines.

Renewed interest in gold in the late 1890s began the area’s most prolific era. By the early 1900s numerous mines were opened. The biggest ones—Silver Lake, Iowa-Tiger, Gold Prince and Sunnyside—employed several hundred men. Large stamp mills and eventually newly invented flotation mills were built to extract the gold and concentrate the ores. Aerial trams moved rock from the mines to the mills below, and the railroad took concentrates to the smelter in Durango. Innovations occurred with the invention of machinery run by electricity or compressed air, such as hoists or drills. This boom ended when the demand for metals decreased at the end of World War I.

The price of gold rose from $20 to $35 an ounce in the 1930s, and demand for base metals increased during World War II, triggering a new epoch of small mining in the area. The largest producer was the Shenandoah Dives Mining Company. Though the company’s ores were low-grade at the Mayflower Mine, manager Charles Chase was able to keep the mine working from the late 1920s until the early 1950s through innovative and cost-efficient mining techniques.

The price of gold rose from $20 to $35 an ounce in the 1930s, and demand for base metals increased during World War II, triggering a new epoch of small mining in the area. The largest producer was the Shenandoah Dives Mining Company. Though the company’s ores were low-grade at the Mayflower Mine, manager Charles Chase was able to keep the mine working from the late 1920s until the early 1950s through innovative and cost-efficient mining techniques.

Small-scale mining saw a brief resurgence during the Korean Conflict but stopped at the end of the war. The Sunnyside Mine was reopened in 1959 by the Standard Metals Corporation and employed over 300 men and women at its peak. It was mined for over three decades, surviving bankruptcies, shutdowns and a devastating flood in 1978 from overlying Lake Emma. It was closed in 1991.

Silverton’s mining heritage can still be experienced at the Old Hundred Mine Tour, the San Juan Historical Society’s museums, and the Mayflower Mill.

Photography

Gold King Mill, San Juan County. Courtesy San Juan County Historical Society, All rights reserved.

Scott Fetchenhier is the author of Ghosts and Gold—The Story of the Old Hundred Mine (Packrat Publishing, 1999).

References & Additional Links

Hard Rock Mining, Silverton Magazine.