Burnham Trading Post

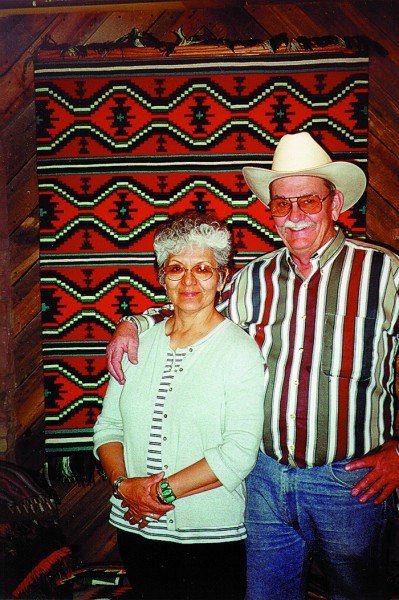

Bruce, Virginia & Sheri Burnham, traders

Story, Kathryn Burke, Photos, James Burke

Sanders, Arizona

The building is just 25 years old; the business dates back more than a century. The now-fifth generation trading family began in the late 1800s with George Franklin Burnham, who was sent, like many other traders of the era, by the Mormon Church to establish a remote mission. “He had a calling,” explains present-day trader Bruce Burnham. “He and his brother moved to Kirtland, NM to establish a town there. My great great Uncle Clinton Luther Burnham was the first Mormon Bishop there. My grandfather, George Franklin Burnham, was told to stay and help support the church, to establish rapport with the Indians and open avenues of trading and commerce with the “lamonites,” or Native American people. My grandfather Roy Barnet Burnham was the first trader in our family to build a store on the [Navajo] reservation. He had a ranch operation and store at Tsaya (north of Crown Point, NM) near the Two Grey Hills area. Later he and my father Roy Burton Burnham had the Burnham Trading Post and Bisti Trading Post. When I was five, my father sold them to move to town so we could go to school in Farmington, NM. He was a good Indian trader, honest to a fault. When he died, they dedicated the Navajo Hour (local radio program) to him for a week! Dad was born and raised on the reservation. He was fluent in Navajo and had a lot of close friends who were Navajo.”

Bruce Burnham is a consummate story teller as well as a trader. As he relates this story, he relaxes in his trading room, still wearing his trademark white Stetson. He is a big man, dwarfing his lovely Navajo wife, Virginia, who comes in occasionally to discuss a customer’s trade. The room is bright with Navajo rugs, the traditional, soft-colored vegetal-dyed Burnt Water, for which the post is known, and the colorful ‘eye dazzler’ contemporary rugs, woven with aniline (chemically dyed) wools from Germantown, Penna., which Bruce is encouraging his weavers to make. There is a distinctive aroma, a combination of old wool and chemical dyes, worn wood and aging stucco that is indigenous only to the generational trading post. And although the building may be fairly new, by post standards, many of the rugs, baskets and old pawn jewelry are not—so the rich patina of color and smells is very much present.

Bruce—his first name is also Roy like his father—stepped comfortably into his heritage. He is the only one of his siblings to go into trading, having done so after getting out of the army. By then, his father had moved to Farmington, NM, where he was a trader. After a brief stint in San Francisco, and exploring alternative lifestyles in Haight Ashbury, Bruce became a trader too, working at several posts before establishing his own at Sanders, just off the reservation. “None of us, except Bill Malone out at Hubble, trade on the reservation anymore,” Bruce laments. “We’re close to the end of a special way of life. When the old people are gone, the trading business, like it was for so many generations, will be mostly gone too.”

Bruce—his first name is also Roy like his father—stepped comfortably into his heritage. He is the only one of his siblings to go into trading, having done so after getting out of the army. By then, his father had moved to Farmington, NM, where he was a trader. After a brief stint in San Francisco, and exploring alternative lifestyles in Haight Ashbury, Bruce became a trader too, working at several posts before establishing his own at Sanders, just off the reservation. “None of us, except Bill Malone out at Hubble, trade on the reservation anymore,” Bruce laments. “We’re close to the end of a special way of life. When the old people are gone, the trading business, like it was for so many generations, will be mostly gone too.”

But not quite. Although Bruce’s son Roy Brent Burnham, has gone into publishing, his daughter Sheri Burnham, now working with him in the business, carries on the tradition, representing the fifth generation of Burnham traders.

Colonization and religious overtones were a common cause of Indian traders, mostly Mormon, who established posts on the Navajo reservation following the Navajo’s return from Bosque Rendondo in the summer of 1868. The Navajo had been banished from their land to Fort Sumner, where deprived of food and other resources, they were literally starving to death. After four years, less than 8 thousand remained! (Today’s Navajo population surpasses a quarter million people.) “The Mormons sympathized with the plight of their lamonite brothers, and so were not granted trading licenses on the reservation until Ulysses S. Grant left office,” Bruce explains. Once those restrictions were lifted, Indian trading began in earnest. Soon the entire northeastern quadrant of the Navajo reservation was served by Mormon traders.”

Meanwhile, many tribes had assimilated into other groups, combining cultures. “The Navajo were especially adept at this,” Bruce says. “They became strong, taking in all that was good from other cultures, rejecting that which was bad. They adapted and adopted from other cultures. From the Spanish, they learned silversmithing. From the Rio Grande Weavers of New Mexico, they adopted rug weaving.”

Bruce credits his decision to become a trader, like his father, grandfather and great grandfather before him, to traders like Jim McJunkins. “He was my hero,” Bruce says. And hero too, to many others who still remember McJunkin from his days as a trader at Teec Toh (in the area where today Navajo and Hopi are in dispute over ownership of adjoining reservation lands.) “McJunkins was 13 years old when he first came out here in the early 1920s,” Bruce relates. “He was looking for a way to eat, headed toward Salt Lake City, but took a wrong turn down an old dirt road. A Navajo man picked him up, took him home and fed him, then took him to Teec Toh Trading Post. McJunkins spent the rest of his life there, in that one building, until he was 90 years old!

“I was visiting him one day—we were sitting in the back—when a kid came in, got what he needed, rang up the sale in the cash register, and went out again. Old Jim didn’t even look up. It was one of the kids he had ‘raised.’

“I was visiting him one day—we were sitting in the back—when a kid came in, got what he needed, rang up the sale in the cash register, and went out again. Old Jim didn’t even look up. It was one of the kids he had ‘raised.’

“Years later, when I wanted to buy the trading post from him, we went to the bank in Winslow (Ariz.) so I could borrow the money. While we waited for the banker to take care of some paperwork, Jim was pacing the floor and sweating. ‘Bruce, I can’t sell the store to you,’ Jim finally said. ‘We can’t leave. This is our home.’ So Jim and his wife, who was sick by then, stayed on. They lived and died there, and when they were gone, the post just kind of blew away. Most of the people have been relocated. You can see why he’s my hero though. I wouldn’t even dream of leaving here (Burnham Post in Sanders, Ariz.) now.

“This is my home, my community. My wife, my children, we are a part of it. It’s an awesome responsibility. We’re here to help, to read or write letters, to help the people we trade with. One writer for another magazine came in here and watched as a woman came in to cash her check and placed her thumb first on the ink pad, then on the back of the check. That thumb print was her endorsement The writer was blown away!”

The Navajo word for Indian trader translates to “the man who sits on the treasure.” “It’s a reverse concept of marketing,” Bruce says. “We guard and protect. It’s socialism at its best.” The Navajo share what they have, keeping only enough for their immediate needs. Their culture is selfless, based on mutual need, described by one powerful Navajo word, “ashonda,” which means “we are obligated to help each other.” There is no Navajo word for “please.” “When we tried to Emily Postize the children, we took away their traditions, undermined their cultural identity,” Bruce believes. “It is our job as traders, to protect and preserve as much of that heritage and tradition as we can. Even though we are in the twilight of Indian trading, we must safeguard the last of a world that is hugely diminishing. We are in the last days of Indian trading.”

Maybe, but Bruce Burnham, and his daughter Sheri who follows him, won’t let it come to an end. They will stay, and the Indian trading tradition will stay with them.

Burnham Trading Post, Highway 191, Sanders, Ariz. 520 688-2777.